A Quarter Century of Emerging-Markets Investing

At one time or another, every country could have been classified as “emerging.” Back in the 1800s, the Western part of the United States was called the “new frontier.” Investors purchasing farmland there were likely to consider it a highly speculative venture putting stakes in such a rugged and wild place. As recently as the 1960s, one could classify Japan as an emerging market, perceived to be a place of cheap exports, a weak currency and an unstable political future. Investing there at that time was considered risky and pioneering, and no doubt there were bargains to be had if you were very selective, and patient. Likely, few would have envisioned that Japan would rise so quickly post-World War II to become a technological leader and global power. China, too, has seen an incredibly rapid economic transformation in the past few decades that probably few would have envisioned.

The investment potential of developing markets had been recognized for a long time, but the actual birth and classification of emerging markets as an investment category in a more formal or recognized way probably could be tied to an event in more recent history. In 1986, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a World Bank subsidiary, engaged in a campaign to encourage capital market development in the less-developed countries, which had often been given unflattering designations such as “third-world” nations. At that point in time, a handful of institutional investors invested US$50 million in an emerging markets strategy at the behest of the World Bank’s IFC. A year later, in 1987, there were two other milestones in the history of emerging-markets investment: MSCI developed its first emerging-markets indexes,1 and perhaps more importantly from our perspective, the Templeton Emerging Markets Group began managing portfolios to allow mainstream investors access to emerging markets.

When we started managing emerging-markets portfolios, it was a difficult time to invest in many respects. Although there were many emerging-market countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe that looked exciting to us, very few of them were actually open to foreign investment. There were strict foreign exchange controls and limitations, in addition to a plethora of problems with market liquidity, corporate governance and safekeeping of securities. In our early days of emerging-markets investing, there were only a few markets available to us. We often had trouble putting our money to work. From an investment standpoint, many emerging markets started essentially as exclusive clubs for the wealthy few, but we’ve seen a rapid growth of egalitarian, open-market practices that today attract a wide audience of global investors.

I can recall back in the early 1990s, for example, trading on Russia’s stock market began around three o’clock in the afternoon, when a luxury vehicle would pull up to the stock exchange building carrying lots of cash. Brokers would sit at long tables waiting for citizens who had been given share vouchers—which could be exchanged for shares in newly privatized Russian companies—to sell them on the exchange. At around six o’clock in the evening, the vehicle would return to collect the vouchers the brokers had bought on the cheap. As investors there ourselves, at the time we faced an extremely unstable environment and were often told “trust us!” with little basis to go on. The vast majority of Russian stocks were so thinly traded we had to wait days, or even weeks, to execute a trade. How things have changed! Today, investors can trade in a wide range of equities, options and commodity futures products on an electronic platform, day and night, not only in Russia but in emerging-market countries around the world.

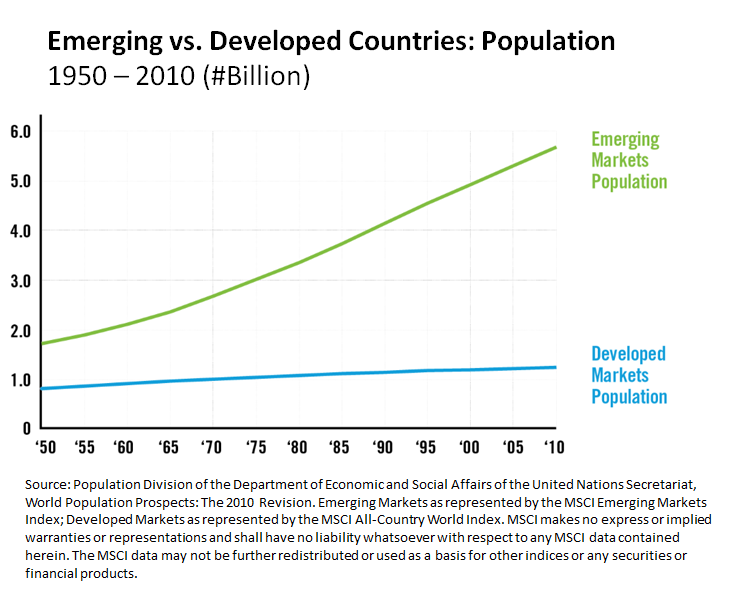

We were there at the start of many exciting developments, which included the opening of many markets to wider foreign investment. In the past 25 years, we’ve also seen the end of apartheid in South Africa, easier access to eastern European economies (including Russia), the opening up of India to foreign investment and, of course, China’s embrace of capitalism and rapid urbanization. Today we can invest in a wide variety of emerging markets around the world, as well as a host of “frontier markets,” a designation given to the lesser-developed subsector of emerging markets, which includes the majority of the African continent. We are very excited about the potential for these frontier countries in the next 25 years, as many are growing at a rapid pace and quickly assimilating the latest technological advancements, particularly in mobile finance and e-commerce. Generally more youthful and growing populations mean consumer power has been on the rise, with a growing middle class.

Reasons for Optimism

The Templeton emerging-markets investment team has grown from just three portfolio managers/analysts some 25 years ago to 52 today, and we have expanded our on-the-ground presence from just one research office in Hong Kong (opened in 1987) to 18 offices in locations including Asia and the Middle East, Europe and Latin America.

There will always be challenges in any country; developed countries certainly aren’t immune to issues like corruption, and temporary market and economic setbacks. Throughout short-term challenges, we’ve remained focused on the long term and on our conviction of the potential we believe emerging markets hold. We also believe in the importance of being on-the-ground, assessing the situation first-hand and talking to individual businesses within a country to determine their distinct fundamentals and potential. This can bring valuable insights you can’t get by analyzing reams of data. For example, on a recent visit to a country in Africa, my team and I were exploring a food and beverage company, and the management had put together a good investment pitch. However, when visiting a local supermarket, we noticed its products were buried on a hard-to-find, lower shelf, making it difficult for consumers to find the company’s product.

Another contrasting example: Visiting Brazil in 1995, I sensed malaise among business leaders given economic challenges there, with slow growth and a recent history of hyperinflation. However, when I spoke with a woman on the street, I got a more upbeat view of the country. She said that with consumer inflation rates running in triple-digit percentage rates the year prior, she didn’t know how much she was going to get paid, due to the country’s indexing system for salaries. At the time of my visit, the inflation trend was starting to decelerate into the mere double-digits, something that she was quite excited about. She said she now didn’t have to rush to the bank anymore to get her cash then rush to the store to buy all her groceries before her money lost its value. Now, she could plan ahead. Statements like this gave me more hope consumer sentiment was improving, and that the economy could recover.

I think the welcoming of foreign capital and the trend toward privatization have been key to the growth and development of emerging markets over the past few decades, and one of my biggest fears is the possibility of the door shutting on both in some countries. Aside from that possibility, as we see it, there are three key reasons to remain optimistic today about the potential emerging markets generally hold.

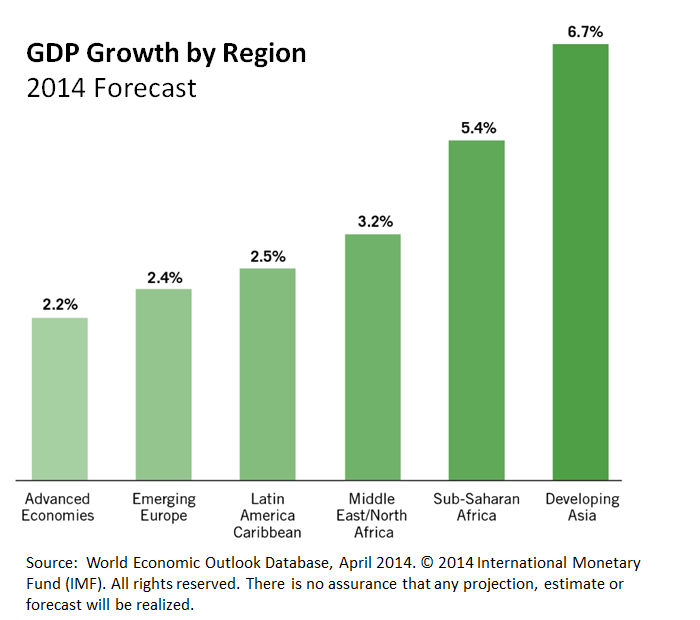

- Emerging markets in general have been growing 3-5 times faster than developed countries; many frontier markets have seen even higher growth.2

- Emerging markets generally have greater foreign reserves than most developed countries.3

- Emerging markets’ debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios are generally much lower than developed markets.4

Put all this together, and we believe there’s a good case to be optimistic about the future for emerging and frontier markets, and we believe their share of the global investable universe will continue to grow. Just imagine what the next 25 years could bring!

Mark Mobius’ comments, opinions and analyses are for informational purposes only and should not be considered individual investment advice or recommendations to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. Because market and economic conditions are subject to rapid change, comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of the date of the posting and may change without notice. The material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region, market, industry, investment or strategy.

Important Legal Information

All investments involve risks, including the possible loss of principal. Investments in foreign securities involve special risks including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments. Investments in emerging markets, of which frontier markets are a subset, involve heightened risks related to the same factors, in addition to those associated with these markets’ smaller size, lesser liquidity and lack of established legal, political, business and social frameworks to support securities markets. Because these frameworks are typically even less developed in frontier markets, as well as various factors including the increased potential for extreme price volatility, illiquidity, trade barriers and exchange controls, the risks associated with emerging markets are magnified in frontier markets. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions.

1.The MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI All Country World Indexes were launched on Dec 31, 1987. Source: MSCI. MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indices or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, reviewed or produced by MSCI.

2.Source: IMF World Outlook Database, April 2014. © by International Monetary Fund. All Rights Reserved.

3. Ibid.

4.Ibid.

Mark Mobius

Mark Mobius, Ph.D., executive chairman of Templeton Emerging Markets Group, joined Templeton in 1987. Currently, he directs the Templeton research team which is based in 18 global emerging markets offices, and manages emerging markets portfolios. Dr. Mobius has been investing in global emerging markets for more than 40 years and has received numerous industry awards, including being named one of Bloomberg Markets Magazine’s “50 Most Influential People” in 2011.

Related Articles

Miscalculations and Recalculations

The market lens for the rest of 2022 will be focused on the impact of political and policy miscalculations, according

Emerging Markets in the Digital Age

My colleagues and I have been actively speaking about the evolution taking place in many emerging markets over the past

Emerging Markets Third-Quarter Recap: A Stellar Rally

Templeton Emerging Markets Group has a wide investment universe to cover—tens of thousands of companies in markets on nearly every

Cool + for the post